When it comes to percutaneous procedures—those minimally invasive medical interventions that involve accessing the body through a small skin puncture—the unsung hero is often the catheter sheath. Far more than just a tube, these sophisticated devices are the vital conduits that facilitate a myriad of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, from coronary angiography to complex structural heart interventions. Mastering the intricacies of Catheter Sheath Types and Design Principles isn't just an academic exercise; it's fundamental for clinicians seeking optimal patient outcomes and for engineers pushing the boundaries of medical innovation.

Without a precisely engineered sheath, the delicate work of guiding wires, balloons, stents, and other catheters through the tortuous pathways of the human vasculature would be significantly riskier, more challenging, and less efficient. This guide will demystify the science and artistry behind these essential access tools, empowering you with a deeper understanding of what makes a sheath truly excel.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways

- Sheaths are More Than Tubes: They are sophisticated, multi-layered devices essential for safe and efficient vascular access in minimally invasive procedures.

- Design is Intentional: Every aspect, from material choice to manufacturing process, is driven by specific user needs and functional requirements like flexibility, kink resistance, and lubricity.

- Layers of Innovation: Most advanced sheaths have inner, reinforcing, and outer layers, each optimized for different performance characteristics.

- Material Matters: The inner layer's material (PTFE, FEP, HDPE, etc.) dictates lubricity, flexibility, and manufacturing feasibility.

- Strength in Structure: Reinforcing layers (braid, coil) are crucial for torque control, pushability, and preventing kinking.

- Diverse Types for Diverse Needs: Sheaths are classified by puncture site (radial, femoral), material, and length, with specialized options for unique challenges.

- Safety First: Sterilization methods (EtO, Gamma, E-beam, Autoclave) are critical, and material compatibility determines the best approach.

- Collaboration is Key: Effective sheath design is a collaborative effort between engineers, clinicians, and regulatory experts.

The Silent Workhorse: Understanding the "Why" Behind Catheter Sheaths

Imagine trying to navigate a narrow, winding river in a flimsy boat without a paddle. That's a bit like performing a transvascular intervention without a properly designed catheter sheath. These devices are the stable, protective tunnels that allow medical instruments to reach their target safely, minimizing trauma to the vessel wall and providing a reliable pathway for multiple exchanges of instruments. They maintain hemostasis, prevent air embolism, and streamline complex procedures. Their importance cannot be overstated in modern interventional medicine.

The Blueprint: Core Principles Guiding Catheter Design

Before a single material is chosen or a manufacturing line spun up, the journey of a catheter sheath begins with meticulous planning. This isn't just about making "a tube"; it's about engineering a precise solution for a specific clinical challenge.

The planning stage covers several critical checkpoints:

- Pre-study and Intended Use: What exactly will this sheath be used for? Which vessels? What types of instruments will pass through it?

- User Needs: What do the clinicians performing the procedure require? Easier access? Better torque control? Smaller outer diameter?

- Functional Requirements Definition: Translating user needs into measurable engineering specifications.

- Device Classification: Determining its regulatory class, which impacts testing and approval pathways.

These initial steps form the bedrock for defining the design input requirements. Think of it as creating a detailed architectural plan before laying any bricks.

Key Performance Characteristics That Drive Design

Every design decision for a catheter sheath hinges on optimizing a delicate balance of performance characteristics. These aren't just buzzwords; they're the benchmarks against which a sheath's success is measured in the demanding environment of the human body:

- Wall Thickness & Diameter/French Size (OD/ID): The critical balance between a thin wall (allowing a larger internal lumen for a given outer diameter) and sufficient structural integrity. Measured in French (F) size, where 1F = 0.33mm.

- Atraumatic Access: The ability to navigate vessels without causing damage. This often involves tip design and material flexibility.

- Lubricity: How smoothly other devices (guidewires, catheters) can pass through the sheath lumen, reducing friction and potential damage.

- Flexibility: The ability to bend and conform to vessel anatomy without kinking. Essential for navigating tortuous paths.

- Kink Resistance: The sheath's capacity to maintain its open lumen even when sharply bent. A kinked sheath is a non-functional sheath.

- Push Strength (Pushability): How effectively force applied at the proximal end (outside the body) is transmitted to the distal end (inside the body) for advancement.

- Torque Transfer (Torquability): The ability to transmit rotational forces from the proximal end to the distal end, allowing for precise steering and positioning.

- Tensile Strength: The resistance to breaking under tension, crucial when withdrawing the sheath or dealing with unexpected resistance.

Beyond these functional attributes, practical considerations like manufacturability, assembly processes (Design for Manufacturing - DFM; Design for Assembly - DFA), and the complexities of sterilization and FDA regulatory considerations are woven into every stage of the design process. An ingenious design that can't be reliably manufactured, assembled, or sterilized won't make it to the patient.

Inside Out: Deconstructing the Catheter Sheath's Layers

Advanced catheters, including sheaths, are rarely monolithic. Instead, they are typically multi-layered marvels of engineering, each layer contributing specific properties to the overall performance. Picture a high-performance tire with multiple plies and compounds; a catheter sheath shares this layered complexity.

The Inner Sanctum: Inner Layer Materials & Their Superpowers

The innermost layer of the sheath, directly contacting the guidewire and subsequent instruments, is paramount for ensuring smooth passage. Its material selection dictates not only lubricity but also manufacturing feasibility and sterilization compatibility.

Let's explore the common champions:

- PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene): The gold standard for lubricity, PTFE boasts the lowest coefficient of friction. This "slipperiness" makes it ideal for thin-wall designs where minimizing resistance is critical. However, it typically requires manual assembly and etching (a surface treatment) to promote adhesion to other layers. Sterilization-wise, EtO (Ethylene Oxide) and autoclave methods are suitable.

- FEP (Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene): A close relative to PTFE, FEP offers good lubricity, though slightly less than PTFE. Its greater flexibility makes it suitable for both single and multi-durometer designs (meaning sections with different flexibilities). FEP has an advantage in manufacturing, as single-durometer and some multi-durometer designs can be continuously manufactured, though etching is still required for optimal adhesion. It's a versatile choice, compatible with all four main sterilization methods: Gamma, EtO, E-beam, and Autoclave.

- ETFE (Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene): Sitting in the mid-range for lubricity, ETFE shines with high tensile strength and excellent impact resistance. Like FEP, single-durometer ETFE designs can utilize continuous manufacturing, but etching is necessary. It, too, is compatible with all four major sterilization methods.

- HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene): Offering good lubricity (though less than the fluoropolymers), HDPE provides significant manufacturing and assembly benefits. Continuous processes are often possible, especially for single-durometer designs, and crucially, etching is not required. This simplifies production and reduces cost. HDPE is suitable for Gamma, EtO, E-beam, and Autoclave sterilization.

- Polyamides (Nylons): These materials are characterized by high strength, making them excellent for thin-wall applications or those requiring high pressure. Single-durometer designs are typically manually processed. An important consideration for polyamides is sterilization: E-beam is generally not suitable, but Gamma, EtO, and autoclave can be used, depending on the specific polyamide grade and other design features.

The Backbone: Reinforcing Layer for Strength and Control

The middle, reinforcing layer is where the sheath gains its structural integrity, preventing collapse, kinking, and ensuring effective force transmission. This layer is critical for turning a simple tube into a precision instrument.

Two primary reinforcement methods are employed:

- Braid Reinforcement: Imagine a finely woven mesh. Braid reinforcement significantly improves torque control, allowing clinicians to precisely transmit twisting actions from the handle to the distal tip for steering. It also enhances push strength, ensuring the sheath can be advanced without buckling. The density and angle of the braid can be customized to fine-tune these properties.

- Coil Reinforcement: Picture a tightly wound spring. Coil reinforcement primarily enhances push strength, providing axial stiffness. More importantly, it dramatically improves kink resistance, preventing the lumen from collapsing when the sheath bends sharply. It also contributes to hoop strength, resisting external compression.

Often, designers will cleverly combine braid and coil reinforcement in different sections of a single sheath. Furthermore, variation in pitch (the tightness of the weave or coil) along the shaft is common. A tighter pitch proximally might offer more push and torque, while a looser pitch distally might allow for more flexibility and trackability around curves.

The Protective Shell: Outer Layer Considerations & Adhesion

The outermost layer of the catheter sheath is the first point of contact with the patient's anatomy and the environment. It must be biocompatible and robust. A primary design challenge here is preventing delamination—where the outer layer separates from the inner layers. This makes the adhesion method and careful material selection absolutely critical. Advanced bonding techniques, surface treatments, and compatible polymer chemistries are employed to ensure the layers remain integrally connected throughout the sheath's lifespan, from manufacturing to clinical use. Hydrophilic coatings, often applied to the outer layer, further enhance lubricity upon contact with bodily fluids, aiding in atraumatic insertion.

Ensuring Safety: A Deep Dive into Sterilization Options

A medical device, no matter how perfectly designed, is useless—and dangerous—if not sterile. The choice of sterilization method is a crucial design input, as not all materials are compatible with all methods. This directly impacts material selection for all layers.

Here are the four main contenders:

- Gamma Sterilization: Utilizes gamma rays from a Cobalt-60 source. It's highly penetrating and effective. The process typically takes several hours. While powerful, some polymers can experience material degradation (e.g., changes in color, embrittlement) from radiation exposure, so material compatibility is key.

- EtO (Ethylene Oxide) Sterilization: A gas sterilization method popular for heat and moisture-sensitive devices. EtO is highly effective at low temperatures. However, it's a slower process, often taking several days due due to necessary aeration phases to remove toxic gas residuals. Environmental and safety concerns regarding EtO emissions are also driving research into alternatives.

- E-beam (Electron Beam) Sterilization: This method uses accelerated electrons. It's one of the fastest sterilization methods, often completed in minutes. Like Gamma, it's a radiation-based method, so material compatibility to electron exposure is critical. Its penetration depth is less than Gamma, making it suitable for devices with lower density or thinner profiles.

- Autoclave Sterilization: This uses high-pressure, high-temperature steam. It's rapid, typically under an hour, and environmentally friendly. However, it's only suitable for devices and materials that can withstand high heat and moisture without degrading or deforming. Many advanced polymer-based sheaths would be damaged by autoclaving.

Beyond the Basics: Classifying Catheter Sheaths by Function and Form

While the internal design principles are universal, catheter sheaths manifest in a wide variety of types, each tailored for specific anatomical sites, procedural requirements, and instrument sizes. Understanding these classifications helps both clinicians choose the right tool and designers innovate for unmet needs.

By Site of Puncture: Navigating Different Arteries

The vessel chosen for access significantly impacts the required sheath characteristics, particularly its diameter and flexibility.

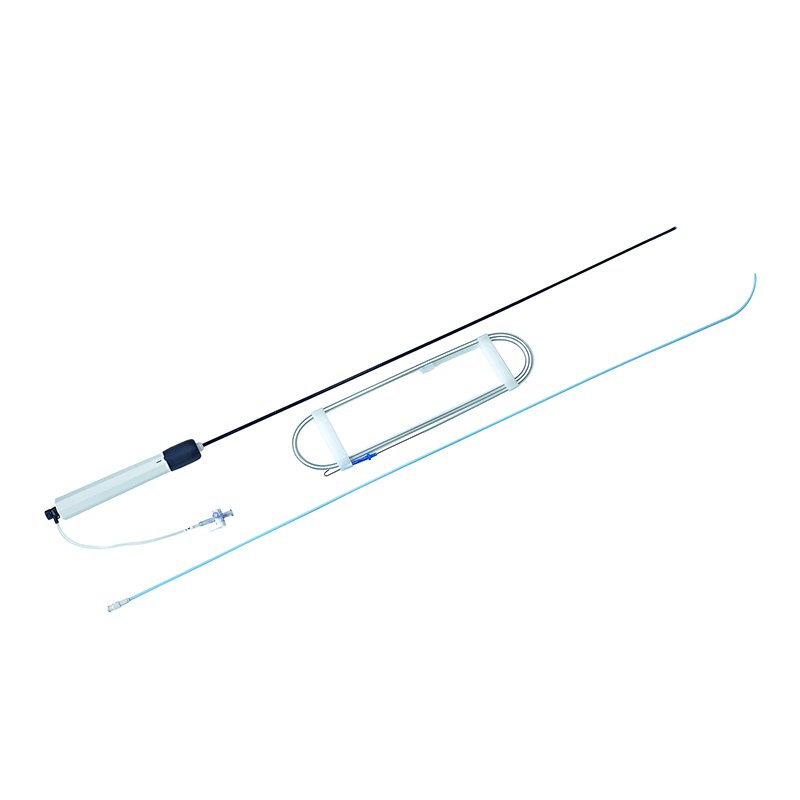

- Radial Artery Sheaths: Accessing the radial artery in the wrist is a common approach for many interventional procedures due to reduced bleeding complications and earlier patient mobilization. Radial sheaths are generally smaller in outer diameter (OD), typically ranging from 4F-7F. The most common sizes are 5F and 6F, with 7F sometimes used for larger male patients or specific device delivery. Their smaller size necessitates thinner walls and often greater flexibility.

- Femoral Artery Sheaths: The femoral artery in the groin has historically been the primary access site and is still favored for larger devices or procedures requiring straighter access to the aorta. Femoral sheaths are generally 4F and above in OD, accommodating a wider range of larger instruments. They often prioritize push strength and kink resistance due to the larger, more tortuous path they might need to traverse in the pelvis.

By Material Composition: Single-Layer vs. Reinforced Strength

The discussion of inner, reinforcing, and outer layers primarily describes metal-reinforced sheaths. However, simpler single-layer polymer sheaths still exist, particularly for less demanding applications.

- Single-Layer Polymer Sheaths: These are typically made of materials like PE (Polyethylene), PTFE, or FEP, extruded as a single tube.

- Pros: Low production cost.

- Cons: Characterized by weaker bending resistance, making them prone to lumen bending or collapse when encountering resistance or tortuosity. They also offer weaker support for instrument delivery.

- Metal-Reinforced Sheaths: As discussed, these incorporate braid or coil reinforcement, often covered with a hydrophilic coating on the outer layer.

- Pros: High production cost (due to complexity), but this translates to strong bending resistance, minimal lumen deformation, and superior support for instruments, torque control, and pushability. These are the workhorses of complex interventional procedures.

By Length: Short Bursts vs. Long Journeys

The required length of a sheath depends entirely on the distance from the access point to the target anatomy and the need to cross various anatomical landmarks.

- Short Sheaths: Ranging from 4F-14F in size and 7cm-25cm in length, these are suitable for general vascular puncture, imaging, and procedures where the target is relatively close to the access site (e.g., in the proximal vessels).

- Long Sheaths: With sizes from 4F-26F and lengths of 25cm or more, long sheaths are indispensable for long-distance puncture points. They are used to cannulate vessels deep within the body, cross bifurcations, or provide extended support and protection along a lengthy vascular segment. For instance, in some complex aortic procedures, a long sheath might extend from the femoral artery all the way into the ascending aorta.

Specialized Sheaths: When Standard Isn't Enough

Innovation continually addresses specific clinical challenges, leading to highly specialized sheath designs:

- Tearable Sheaths: These unique sheaths are designed to be "peeled" or torn longitudinally from the outside once the device (e.g., a pacemaker lead or a large bore catheter) has been delivered. This is crucial when the sheath cannot be left in situ because its diameter is too large to remain safely in the vessel or if components attached to the delivered device prevent its removal through the sheath. The tearable design allows for clean, atraumatic removal.

- Thin-Walled Sheaths: These sheaths represent a triumph of material science and extrusion technology. For a given French size (meaning the same outer diameter), a thin-walled sheath has a smaller wall thickness. This seemingly minor change translates into a significantly "larger lumen" internally, allowing for the passage of larger instruments or providing more working space, all while maintaining a smaller, less traumatic outer diameter. This innovation is especially vital in smaller vessels or when maximizing the internal working channel is paramount.

- Overtop Sheath: This is a specific type of long vascular sheath, typically used to provide support for vascularization of the contralateral limb (the opposite side of the body from the access point). It's designed to be advanced across the main bifurcation of the guidewire catheter, offering stable access and support in complex cross-over techniques, often seen in peripheral arterial disease interventions.

The Design Journey: From Concept to Clinical Reality

The development of a new catheter sheath is a complex, iterative process that demands close collaboration between engineers, material scientists, manufacturing specialists, and clinicians. The principles of Design for Manufacturing (DFM) and Design for Assembly (DFA) are not afterthoughts but integral to the design process. Can this sheath be produced efficiently, consistently, and cost-effectively? Can its various layers be assembled reliably at scale? These questions drive choices in materials, layering techniques, and even the final geometry of the sheath.

Beyond the technical hurdles, the regulatory landscape is equally demanding. In the US, the FDA requires rigorous testing and documentation to ensure safety and efficacy. Each material choice, manufacturing process, and performance claim must be substantiated. This ensures that every sheath that reaches a patient has met stringent quality and performance standards.

The journey continues even after initial approval. Post-market surveillance and continuous feedback loops with clinicians inform future iterations and improvements, ensuring that sheath design remains responsive to evolving clinical needs and technological advancements.

Understanding the principles of catheter sheath irrigation schematics can further illuminate how sheaths are designed for specific operational needs within these complex procedures.

Making the Right Choice: Key Considerations for Clinicians and Designers

For clinicians, selecting the appropriate catheter sheath can profoundly impact procedural success and patient safety. Here's what to consider:

- Procedure Type: What intervention are you performing? Diagnostic angiography, device delivery (stent, valve), aspiration? Each demands different sheath characteristics.

- Access Site: Radial, femoral, brachial, or another? This dictates the initial size and flexibility needs.

- Target Vessel & Anatomy: Is the path tortuous? Are there tight lesions or calcifications? This will influence flexibility, kink resistance, and support requirements.

- Instrument Compatibility: What size and type of guidewires, catheters, and devices will be advanced through the sheath? Ensure the sheath's inner diameter (ID) is adequate.

- Required Support & Torque: Do you need robust support for crossing tough lesions, or precise torque for navigating complex turns? This informs the need for braided or coiled reinforcement.

- Desired Lubricity: For multiple exchanges or delicate instruments, a highly lubricious inner lumen is critical.

- Patient Factors: Size, weight, and existing vascular disease can influence sheath choice.

For designers, the considerations are even broader, encompassing everything from raw material costs and supply chain stability to long-term biocompatibility and environmental impact.

The Future of Vascular Access: Innovations on the Horizon

The field of catheter sheath design is far from stagnant. Ongoing research focuses on:

- Enhanced Biocompatibility: Developing new materials that further reduce inflammation, thrombus formation, and infection risk.

- "Smart" Sheaths: Incorporating sensors for real-time pressure monitoring, temperature sensing, or even drug delivery capabilities.

- Smaller Profiles, Larger Lumens: Pushing the boundaries of thin-wall technology to enable larger device delivery through increasingly smaller access sites, minimizing patient trauma.

- Sustainable Materials & Manufacturing: Reducing the environmental footprint of medical device production.

- Advanced Coatings: Exploring new hydrophilic, antimicrobial, or drug-eluting coatings to improve performance and safety.

These innovations promise a future where vascular access is even safer, more efficient, and less invasive, further expanding the reach of interventional medicine.

The Unseen Hand of Excellence

Catheter sheaths are more than just passive conduits; they are active facilitators of critical medical procedures. Their design principles, rooted in a deep understanding of physics, materials science, and human anatomy, dictate their ability to provide stable access, minimize trauma, and optimize the delivery of life-saving interventions.

From the molecular structure of the inner lining to the weave of the reinforcing braid, every detail contributes to a device that is reliable, predictable, and ultimately, safe for the patient. For anyone involved in vascular access—be it in the operating room or the design lab—a profound appreciation for these intricate tools is not just beneficial, it's essential for advancing the art and science of medicine.